CHIKV vectors are primarily anthropophilic, meaning that they preferentially bite humans. They mainly feed outdoors during daylight hours, but Ae. aegypti has also been known to feed indoors. Ae.aegypti is considered a highly efficient vector because it will often feed on multiple people to obtain a single blood meal (referred to as a “sipper”), compared to other species that will feed on only 1 host to complete a gonotrophic cycle (the process of developing and laying eggs). With this feeding behavior of taking small meals from different people, CHIKV-infected Ae. aegypti females are capable of infecting multiple individuals while obtaining a single meal, which increases transmission events. Aedes albopictus is more of an opportunistic feeder and will readily feed on humans and different types of animals, depending on host availability.

Symptoms

Factors Driving Emergence and Increased Transmission

Climate Change

Female Aedes aegypti mosquito.

Source: cdc.gov, public domain

Viral Adaptation

Approximately 85% of people who become infected with CHIKV will have symptoms, which contrasts with other Aedes-associated viruses, like dengue and Zika virus, where only about 20% will have symptoms. Chikungunya is generally characterized by rapid onset of fever, muscle pain and joint pain. Other common symptoms include headache, nausea, fatigue, and rash. The rash typically begins with flushing of the face and trunk and progresses to macules (red spots) and papules (raised bumps) on the trunk and extremities. Most symptoms last about 1 week, but the joint pain can be intense and last weeks to months in up to 50% of patients. It is thought that the long-term joint pain associated with chikungunya is due to the presence of viral antigens in the joints, leading to a persistent inflammatory response. Joint pain is the hallmark symptom of CHIKV infection and is used for differential diagnoses in regions where other arboviruses co-circulate.

There are many factors that can drive the emergence, reemergence and increased transmission of mosquito-borne arboviral diseases. Numerous factors have been associated with CHIKV outbreaks occurring in new regions and the overall increase in viral circulation, including climate change, viral adaptation and global travel.

Climate change is a major factor affecting mosquito-borne disease systems. Mosquitoes are ectotherms, so they depend on external sources for body temperature regulation and are sensitive to temperature changes. In recent years, global warming has expanded the distribution ranges for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, which both prefer warm, humid climates. The optimal temperature range for these species is between 25-35°C. Rising temperatures, along with increased precipitation, have allowed for the geographic expansion of these vector species, facilitating CHIKV transmission in new areas. In addition to vector movement, higher temperatures can also increase virus replication inside of the mosquito, which results in a shorter EIP. When EIP is decreased, the mosquito is able to transmit the virus faster, leading to more transmission events.

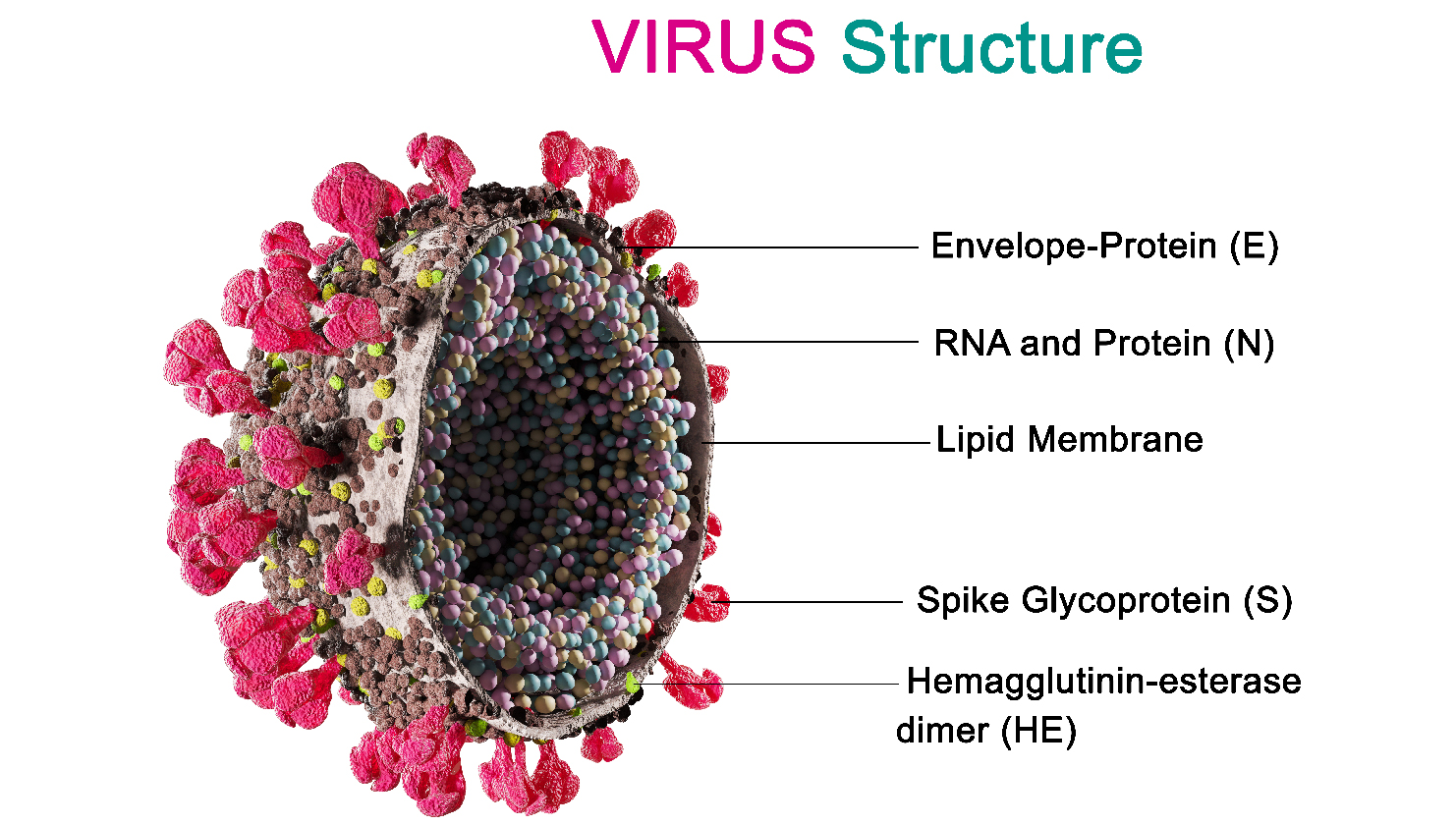

Another factor that can affect CHIKV emergence is viral adaptation. As an RNA virus, CHIKV can readily mutate and adapt under selective conditions For example, adaptation can occur when the virus evolves to survive and thrive in a host species. Genomic analysis has demonstrated that 3 main genotypes of CHIKV have evolved and are circulating globally: the West African genotype; the East, Central and South African (ECSA) genotype; and the Asian genotype. Recent outbreaks reported worldwide are mainly attributed to the ECSA and Asian genotypes. Each of the CHIKV genotypes has differences in pathogenicity, epidemic potential and has historically circulated in the geographic regions after which it is named.

Naming diseases after geographic locations can negatively impact communities and cultures, and often is misleading. Updated guidelines favor generic, symptom-based nomenclature to reduce misconceptions.

In 2005-2006, a large CHIKV outbreak occurred on Réunion Island, located in the Indian Ocean, with over 244,000 cases documented. It was noted that this island had very low populations of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Genomic sequencing was conducted on the circulating strain revealing a point mutation in the E1 (envelope) protein that enabled Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, which are widespread on Réunion Island, to transmit the virus more efficiently. This mutation, at location A226V, was shown to increase viral replication in Ae. albopictus, facilitating the outbreak and highlighting the important role of viral adaptation in increasing transmission.

Global Travel

Global travel can also play a critical role in viral emergence. The movement of people can facilitate the movement of a pathogen from one part of the world to another. If a CHIKV-infected traveler arrives in an area with vector mosquitoes present and low herd immunity, a new transmission cycle can be established. The spread of CHIKV by infected travelers has been documented as the source of viral introduction on numerous occasions. For example, sequencing analysis demonstrated that the introduction and spread of CHIKV in the Caribbean Islands in 2013-2014, and eventually to the continental U.S., was attributed to the movement of infected travelers. The critical timeframe of infection is when a traveler is viremic (viruses circulating in the blood), which is typically 4-6 days, but can be as long as 12 days, post illness onset. This is when vector mosquitoes can bite the host, ingesting the virus, and begin a new cycle. Monitoring the activity and movement of specific CHIKV genotypes can elucidate how sick travelers play a critical role in viral emergence into new geographic regions.

History of CHIKV Global Circulation

CHIKV has emerged numerous times and established endemic transmission and outbreaks in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. According to the World Health Organization, as of December 2024, autochthonous (local) transmission has been documented in 119 countries and territories worldwide.

Mosquito-borne CHIKV transmission was first documented in the U.S. in 2014, with cases reported in Florida, Texas, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Only 1 autochthonous case was detected in the U.S., in 2015, and after that, only travel-associated cases were reported through 2024. In October 2025, the New York State Department of Health confirmed an autochthonous chikungunya case on Long Island, the first evidence of mosquito-borne CHIKV transmission in the continental U.S. since 2015. With established populations of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus throughout large portions of the U.S., an infected traveler can arrive and begin a new human-mosquito-human transmission cycle. Without any herd immunity, and with limited vaccine resources, a new introduction of CHIKV could result in a major epidemic. Entomological and epidemiological surveillance activities are critical for monitoring and responding to potential CHIKV introductions and outbreak situations.

Treatment

There are no specific antiviral drugs or treatments available for CHIKV infections, so symptom management with acetaminophen or paracetamol followed by a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug is recommended for pain relief and fever reduction.

Prevention

The best way to prevent CHIKV infection is to avoid mosquito bites. There are 2 vaccines available in the U.S., but they are not widely used and only recommended for populations living in or traveling to high-risk areas. The 2 vaccines are IXCHIQ, a live-attenuated vaccine, and VIMKUNYA, a virus-like particle vaccine.

China is employing multiple strategies to decrease CHIKV transmission, as it is currently experiencing the largest outbreak ever recorded. The city of Foshan, at the center of the outbreak, has responded with extreme measures by conducting extensive fogging with insecticides, requiring identification of individuals purchasing medications used to treat chikungunya, releasing Gambusia fish and Toxorhynchites species mosquito larvae into the environment—both of which feed on mosquito larvae—and fining residents with standing pools of water on their property, which could be used as breeding sites.

Final Thoughts

Historically, CHIKV has demonstrated remarkable adaptability. Environmental changes, urbanization and vector adaptation have enabled CHIKV to jump to new hosts and regions, highlighting the interplay between viral evolution and global health dynamics.CHIKV transmission exemplifies the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health, the core principle of One Health. CHIKV transmission depends heavily on the ecology of Aedes mosquitoes (A. aegypti and A. albopictus), which thrive in human-altered environments, such as urban and peri-urban areas with poor sanitation and standing water. Changes in land use, climate change and globalization contribute to the expanding range of these vectors. When we alter ecosystems—intentionally or unintentionally—we often create new opportunities for disease vectors, like mosquitoes, to thrive. Environmental changes can’t be separated from infectious disease emergence. CHIKV is riding the wave of climate instability.

The time is now for all to advocate for a collaborative, cross-disciplinary response to CHIKV outbreaks—uniting clinical microbiologists, entomologists, veterinarians and public health officials. This particular outbreak, as well as those involving other vector-borne pathogens, illustrates that the application of One Health concepts is not optional, but essential for managing emerging infectious diseases in a rapidly changing world.

In a bold step toward climate action, leading microbiology societies and organizations have launched the first joint global strategy to harness microbial life for climate solutions. This landmark strategy has been published across 6 scientific journals, including ASM's open access journal, mBio.